This article is the introduction to a series of pieces on the Sahara Desert. In this piece the author assesses the idea of emptiness and how this has come to be seen as a threat in international politics. In the words of Jonathan Swift, “So Geographers in Afric-maps With Savage-Pictures fill their Gaps”

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By Jack Hamilton, 23 Dec, 2011

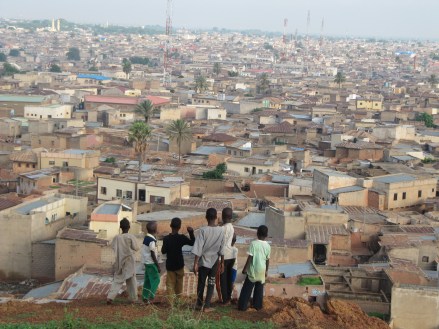

Emptiness is both romanticised and feared. In this sense deserts serve as a geographical blank canvas upon which cultural and political views can be painted. It is this fear of the unknown that ebbs into contemporary political and cultural tropes on the Sahara Desert.

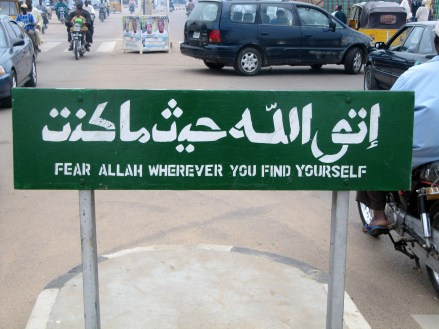

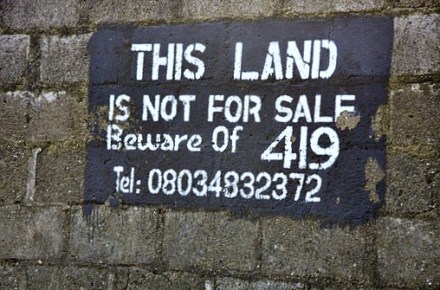

Grazing from Mauritania in the West through the hinterlands of Mali, Algeria and Niger, to the Tibesti mountains of Chad towards the northern states of Nigeria, this is the land which has been described as the ‘swamp of terror’: the Sahara-Sahel. The narrative of this terrain has drifted from romantic imaginings of nomadic caravans and peaceful Sufism towards depictions of drug smuggling routes and sandy bastions of violent Islamism threatening the West. When did the ‘nomads’ become ‘terrorists’?

Security for the Insecure

The increased militarisation of the region makes it important to question how this shift in language has come about since the relatively brief introduction of the Global War on Terror (GWoT) to the area and the reasons as to why this occurred. The current rhetoric used to describe the threat of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) is predicated upon previous linguistic constructions of the Sahara as well as the more recent tropes of the GWoT to create a threat far surpassing the capabilities of the small group in the desert.

That is not to say that AQIM does not exist and is not a threat. It is instead the assertion that the Sahara should be viewed as a diverse region in itself and not merely lumped into the cartography of insecurity put forward under the GWoT.

The Blank Canvas of the Desert

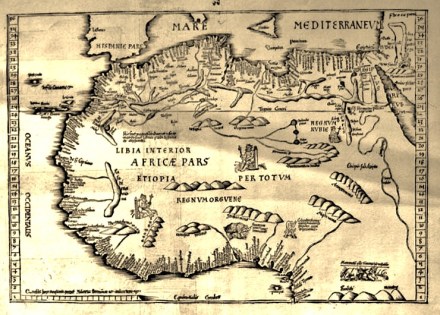

For centuries the unknown hinterlands of the Sahara have been imagined with colourful representations of nomads riding exotic beasts and African kings holding up the famed golden wealth of Africa in their hands.[i]

Defined by its emptiness, religion, wealth and potential threat, the lands to the south of the Mediterranean existed not as a discrete entity but an ebbing shore (or in Arabic, a Sahel) to other civilisations. Such images have faded but the narratives remain. The ‘shore’ now borders a ‘swamp of terror’[ii] that is perceived to traverse the globe, sustained by religion and poverty, to create the cartography of insecurity.

The decision to undertake a war in the Sahara may have been inherently political but the success of the messages of the Global War on Terror have relied on pre-existing tropes synonymous with Africa and the Sahara in particular. The historian, E. Ann McDougall claims that ‘the Sahara has served the West as a canvas on which to paint its greed, fears and ambitions’[iii]. It is upon this cartographic canvas that a small group in the Sahara-Sahel has been constructed as a direct threat to the West.

Geographical Emptiness

Depictions of the Sahara centre on the notion of emptiness. Maps show a land derelict of flora and fauna that isn’t delineated as being ‘North Africa’ nor can it be ‘Sub-Saharan Africa’ by definition. It exists in the margins as it is seen as a margin in itself: a geographical ‘other’. This drought of definitions has been extended into the narratives surrounding the Sahara-Sahel in the GWoT.

Deprived of distinguishing characteristics it has come to be defined by associations, geographical and rhetorical, to explain a region that is simultaneously devoid of life but teeming with insecurity. It is therefore necessary to locate the Sahara-Sahel within the narratives of the GWoT to see where they interact with the ‘Savage-pictures’ to fill this geographical and rhetorical gap.

In this series the ‘emptiness’ of the Sahara will be evaluated by assessing the threat of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb in comparison to the forces being deployed to fight against them. The next article will assess the position of the Sahara in the Global War on Terror and place the region within the global cartography of insecurity.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[i] This most famous of these pictures is in the Catalan Atlas published in 1356, drawn by Abraham Cresques. The original is in the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris and can be also found on the internet at: http://www.georgeglazer.com/maps/world/catalanenane.html. accessed on 28 August 2011.

[ii] Powell, ‘Swamp of Terror in the Sahara’.

[iii] E. Ann McDougall, ‘Constructing Emptiness: Islam, Violence and Terror in the Historical Making of the Sahara’, Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 25 (1: 2007), p. 17.