In this guest post from Andrew Lebovich, the recent events in Mali are dissected from the military coup to the future of the ‘newly liberated nation of Azawad’. Instability in the region is rife and Andrew posits that without a rapid response, the situation is liable to degenerate rapidly.

by Andrew Lebovich, 9 April, 2012

This post was originally published on Andrew’s website, al-Wasat. The website seeks to compile perspectives on the Middle East, South Asia, CT and COIN. Their goal is to bring together some articulate, interesting, and occasionally funny individuals to write about radicalization, counterterrorism, terrorist ideology, Muslims in the West, and regional issues, all in one blog.

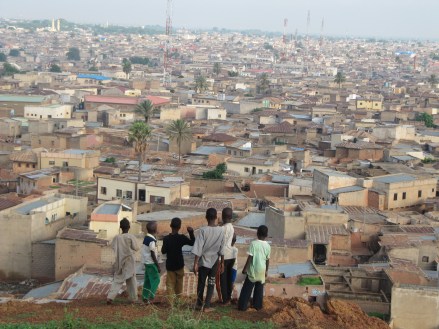

Less than two weeks after a group of Malian junior officers led a coup against the government of president Amadou Toumani Touré, Mali’s war in the north has fallen apart. In a three-day period that ended Monday, Tuareg rebels had seized the three major northern towns of Kidal, Gao, and Timbuktu, victories unparalleled in the past.

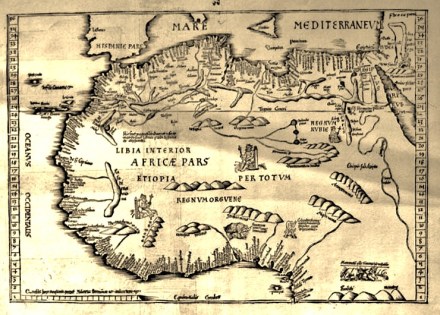

On Thursday, a spokesman for the Malian Tuareg rebel group the National Movement for the Liberation of the Azawad (known by its French acronym the MNLA) said that the group’s fighters had arrived “at the frontier of the Azawad” – a mostly scrub and desert territory the size of France that comprises a diverse ethnic population – and declared a halt to military operations. Later the same day, the group declared the unilateral independence of the region. In a dizzying flourish of events, the war that Tuareg rebels had fought since January 17, the fourth in a series of rebellions that began in 1963, appeared at first blush to be over. Instead, the real fight over the Azawad may have just begun.

The rush to capitalize on the dissolution of Mali’s army in the north has brought to the fore deep conflicts between the MNLA and the salafist-inspired Ansar Al-Din, and brought two terrorist groups who call northern Mali home – Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and its “splinter” group the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJWA) out of the woodwork.

The scant reporting and witness statements emerging from the north paint a confusing and complex picture of events there, one complicated by conflicting agendas and a sheer lack of information, credible or not. But with some reports depicting scenes of destruction, looting, and even rape in Gao and Timbuktu, the imposition of harsh tenets of sharia law in Kidal and Timbuktu, and a possible struggle for control in all three cities, events in northern Mali appear more than ever to be shrouded, to appropriate a phrase used by Tuareg expert Baz Lecocq, in a “haze of dust.”

Known unknowns

As Lecocq astutely pointed out when writing this week about the situation in the north, much of what we see now is based heavily on slim reporting, nearly impossible to confirm witness statements, and assumptions. But with those caveats aside, it is possible to trace at least the broad outlines of how we have arrived at this conflicted point, and where things may go from here.

According to a pro-MNLA writer Andy Morgan, at a meeting in October 2011 in the desert oasis of Zakak, a group of Tuareg leaders met to decide their future course of action in Mali. Comprised of local notables, past rebels, and commanders and fighters recently returned from Libya, this group would soon be known publicly as the MNLA. But at the meeting, Iyad Ag Ghali – the leader of Tuareg rebellions in the 90’s, and later a Malian diplomat in Saudi Arabia and interlocutor in hostage negotiations with AQIM – purportedly presented himself to be head of the MNLA.

Iyad lost that attempt, as Bilal Ag Cherif was appointed the Secretary General of the MNLA. He also reportedly lost a subsequent attempt to lead the Ifoghas tribe, towhich he belongs. Alghabass Ag Intallah, the middle son of the current amenokal, or leader, of the Ifoghas was appointed the tribe’s “chief executive.” It should be noted that Morgan appears to be the sole available source for these particular claims, and the full story is likely far more complicated.

Once known for his love of wine, women and song, Iyad, who grew more religious over the years, went into seclusion after these defeats. In December news leaked that Iyad had created a new Salafist Tuareg group – Ansar Al-Din. Yet little was known or heard from or of Iyad until after the violence broke out in January. Following a siege of the military base at Aguelhoc at the end of January, photos and reports out of the city spoke of “summary executions” of nearly 100 Malian soldiers at Aguelhoc, and France and the Malian government suggested that extremist elements ranging from Iyad’s group to AQIM may have been involved.

Although rumors abounded about the presence of Iyad’s fighters and even those belonging to his cousin, AQIM sub-commander Hamada Ag Hama (Abdelkrim el-Targui), there was little hard proof of Iyad’s role in the north throughout February and early March, even as the MNLA advanced rapidly, picking off border towns with Algeria and Mauritania and harassing towns south of Timbuktu. The MNLA acknowledged quietly that Ansar Al-Din had fought with them at Aguelhoc and elsewhere, but categorically denied links to AQIM, even suggesting that Iyad had helped bring a number of Tuareg AQIM fighters back into the fold and away from jihadist militancy.

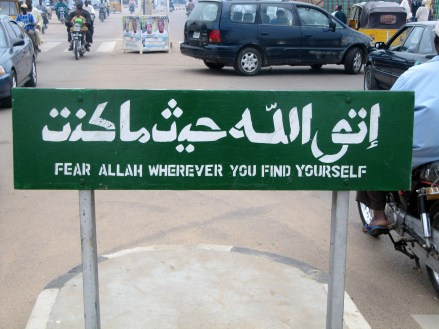

It was not until the strategic town of Tessalit was seized March 11 that cracks began to show. Soon after the MNLA claimed victory at Tessalit, Ansar Al-Din made its media debut on YouTube. The group’s 12-minute video showed images of Iyad leading his men at prayer juxtaposed with images of fighting at Aguelhoc and a message from another historical rebel figure, Cheikh Ag Aoussa, calling for the implementation of sharia not in an independent Azawad, but throughout Mali. A week later the group is said to have released a statement to journalists calling for the implementation of sharia in Mali by “armed combat” if necessary – far from the MNLA’s message of a secular, democratic Azawad. The move prompted the MNLA to distance itself from and then denounce Ansar Al-Din. Tension mounted as the latter claimed responsibility for a series of key victories in the north, which the MNLA and pro-MNLA sources denied vigorously.

Yet it appears that this outward animosity did not stop elements or commanders from these groups from working together, at least in some capacity. As Mali’s army dissolved from within following the March 22 coup d’état, MNLA and Ansar Al-Din forces surrounded Kidal, reportedly pushing into the city from opposite sides after negotiations for its surrender failed. Just a day later the key southern city of Gao fell with hardly a fight, again with reports that a group of fighters entered and seized parts of the city – the MNLA, Ansar Al-Din, and even the AQIM dissident group MUJWA, which according to some reports seized one of Gao’s two military camps, as the MNLA seized the other.

Just a day later Timbuktu, the last military bastion in the north, fell without a fight. While the MNLA had negotiated a peaceful transition with the local Bérabiche (Arab) militia protecting the town, Iyad soon swooped in, reportedly pushing MNLA forces to Timbuktu’s airport, and announcing first to the city’s religious and political leaders – and then on Wednesday, its people – his intention to implement sharia and fight those who oppose it.

Worse still are the reports that Iyad was acoompanied by several very important AQIM commanders: Mokhtar Belmokhtar, Abou Zeid, Yahya Abou al-Hammam, and close Belmokhtar aide Oumar Ould Amaha (spelled Oumar Ould Hama in some reports).

While the MNLA has forcefully denied being expelled from Timbuktu, Iyad’s statements and a number of eyewitness reports appear to confirm his takeover of the city and efforts to enforce the veiling of women, shutter shops and hotels selling alcohol, and even exact harsh punishment on looters and “vandals”. He is also said to have lowered and burned the MNLA’s flag, replacing it with a black “Islamist” flag.

Emerging from the shadows

One of the more startling elements of the reports out of Timbuktu is the aggressive emergence of AQIM on the scene. While AQIM and its predecessor groups, the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC) and the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) have long operated in the Sahara, and have attacked regional armed forces and other targets in Mauritania, Mali, and Algeria, AQIM is known much more for smuggling (drugs, cigarettes, weapons, and more) and the kidnapping of Westerners across the region, operations that may have netted the group tens of millions of dollars.

If true, reports of AQIM leaders appearing so openly in public – let alone this many of them, together – would be unprecedented. Yet it is extremely difficult even to assess these claims. While various accounts cite Timbuktu residents and participants at the Monday meeting identifying the AQIM leaders by sight, eyewitness accounts are notoriously unreliable. Moreover, it would be an extraordinary circumstance for so many key leaders to be in the same place, even if only for a short time. This is especially true given the reputed rivalry between Abou Zeid and Belmokhtar, though I have cast doubt on the extent of their supposed divisions in the past.

Nonetheless, it seems apparent that there is at the moment a sizeable AQIM presence in the city, operating openly alongside Ansar Al-Din and possibly searching for Westerners. Additionally, it makes at least anecdotal sense that AQIM would be both present in the city and useful in supporting Ansar Al-Din.

As I previously mentioned, many analysts believe blood ties exist between Iyad and the AQIM subcommander Abdelkrim el-Targui, who analysts believe is close to Abou Zeid and organized the kidnapping of two French men in the Malian town of Hombori last November. And the two groups share a broad worldview about the implementation of sharia and pursuit of jihad, though significantly less is known about Ansar Al-Din’s core ideology, having only given a small number of public statements.

More apparent, though, is the clear benefit AQIM brings Ansar Al-Din. On the one hand, AQIM can provide dedicated, hardened fighters, a significant factor if estimates that Ansar recently only possessed a few hundred men are correct. More importantly, AQIM may offer Ansar a bridge allowing the group to operate in Timbuktu; both Belmokhtar and al-Hammam have operated for several years in and around Timbuktu, and in particular to the north of the city. Just last month, Mauritanian aircraft struck a convoy they thought included al-Hammam less than 100 km north of the city. And Belmokhtar has, according to most accounts, married a Berabiche woman from a prominent family in or near Timbuktu. Given that Berabiche Arabs are predominant in the city, these longstanding transactional and personal ties – not to mention fear of the organization – could help the primarily Tuareg Ansar Al-Din avoid conflict and exert its influence in the city. It is too early to tell, however, if the tenuous calm in Timbuktu will hold for long.

Less easy to decipher are the gains to be reaped by AQIM or MUJWA from this arrangement. Reporting on the group since the Tuareg uprising has been scarce, though various unconfirmed reports placed Belmokhtar in Libya while others were believed to have fled into southern Algeria, perhaps to pursue business opportunities or simply wait until the instability settled and a clear winner emerged in the north.

The return of AQIM to the battlefield would indicate that they believe that a winner has emerged – though it is difficult to say if AQIM seeks a greater safe haven in which to operate, tighter control over smuggling routes in northern Mali, or simply the chance to spread its own version of Islamic practice. Still, this kind of active and open AQIM presence marks a serious break with past practice, and could herald a shift in AQIM’s behavior, goals, and operations.

This leaves us with MUJWA. The group announced that it had splintered from AQIM in December 2011, criticizing its predecessor organization’s lack of dedication to jihad and promising to spread its operations into West Africa. Interestingly, though, its only known leadership are from Mauritania and Mali, and the group’s only two operations before last week were in Algeria (the October 20 kidnapping of three aid workers from the Polisario-run Rabouni camp) and against an Algerian target (the suicide bombing of the gendarmerie headquarters in Tamanrasset).

The group’s self-proclaimed heavy involvement in the attack on Gao, like with AQIM in Timbuktu, represents a surprisingly overt involvement in the Mali conflict. Unlike AQIM, however, MUJWA has gone out of its way to show off its presence, even appearing before an Al Jazeera camera team in Gao.

We know significantly less about MUJWA, making it harder to discern their motives for playing such a purportedly important role in Gao. It is worth pointing out, however, that one of the group’s leaders, Sultan Ould Badi, is believed to be from north of Gao, which could again be a sign of MUJWA operating, like AQIM, where they have more local support or ties.

And we may get a better sense of MUJWA’s trajectory if allegations that the group was behind the ransacking of Algeria’s consulate in Gao, as well as the abduction of seven Algerian diplomats. Al Jazeera released a video Friday purporting to show MUJWA fighters taking the consul away, as well as shots of the group’s black flag flying over the consulate. This attack shows an unusual focus on Algeria for a group nominally committed to propagating jihad in West Africa, and might indicate that MUJWA remains close in important ways to AQIM.

Iyad and the MNLA

While the rapid expansion of Ansar Al-Din and other jihadist elements is a major concern to Western countries with a stake in the stability of the Sahel, they pose the most immediate threat to the MNLA’s efforts to secure an independent state in the Azawad.

Ansar’s growing public presence last month caused some to begin to doubt the control the organization said it possessed in the north, especially after a Red Cross convoy invited to Tessalit by the MNLA was turned back by armed men, widely believed to be Ansar Al-Din fighters. The MNLA’s failure to secure Kidal and Gao and the embarrassing loss of Timbuktu only reinforced for many this sense that the MNLA had perhaps exaggerated its fighting strength or leadership in the rebellion.

This fracturing of the Tuareg rebel movement has a few potential explanations. The first is simply that expert estimates of the size of the MNLA fighting force (perhaps as many as 3,000 men, according to Tuareg expert Pierre Boilley) were not accurate. The balance of forces also could have been impacted by the fact that Ansar Al-Din fighters have concentrated their forces on individual battles in Tessalit, Kidal, Gao, and now Timbuku, while MNLA fighters have ranged across northern Mali, from Ménaka in the east to Léré in the west, and from Tessalit in the north to Youwaru in the south.

Another possibility is that the MNLA, despite having a clear structure on paper and an impressive media organization centered primarily (but not exclusively) around Francophone Europe-based diaspora intellectuals, is not a truly coherent fighting organization on the ground. Unfortunately, there is not enough reporting to confirm or deny this theory, though it is telling that the MNLA has sought the help of Ansar Al-Din when engaging in most of its major battles or sieges since January. And in the face of clear affronts, the MNLA has thus far staunchly avoided any action that would lead to violence with Iyad.

In part, this is because taking on Iyad directly poses several potential problems for the MNLA. Setting aside questions about the relative strength of both groups (which we can’t answer at this time) attacking Iyad directly could further erode the MNLA’s cohesion. Despite having compromised with the Malian government after the 1990’s rebellions, Iyad remains an influential figure, owing both to his reputation as a former rebel leader and his position within the Ifoghas, the minority tribe that has nonetheless held sway in Kidal for several centuries (a fact aided by colonial France’s decision to maintain and entrench Ifoghas dominance). While the MNLA and its base of support is not just Ifoghas-based, an attack on such a prominent figure could undercut Ifoghas support.

However, I think the theses that privilege the MNLA’s apparent weaknesses ignore important mitigating factors that could help explain the group’s behavior.

For one thing, it is possible that the MNLA decided that it was better to finish its project of securing the borders of its new state, as it announced Thursday, before moving to solidify its internal position. While this is a risky proposition given the rapid and very public steps Iyad and his allies have taken, it may not be an entirely bad strategy; French Foreign Minister Alain Juppé on Thursday made a clear distinction between the MNLA and its erstwhile allies, calling for talks between Mali’s neighbors and Tuareg rebels combined with efforts to combat terrorism in Mali’s north. Reading between the lines, his remarks hold out the prospect of some sort of international recognition for the MNLA’s cause, especially when seen in the context of past vows by MNLA leaders to deal with AQIM if given an independent state.

Additionally, despite some very visible setbacks, the MNLA hasn’t actually left the field. Radio France Internationale reports, for instance, that the MNLA is quietly trying to restore order in Gao, and meeting with traditional and religious leaders in the city. And despite being pushed out of central Timbuktu, the group still holds the airport, and is, according to some (admittedly pro-MNLA) reports, encircling the city. They have also entered Timbuktu since Ag Ghali’s takeover to spirit three Western expatriates to safety in Mauritania.

Time is running out

The situation in northern Mali remains fluid, and the MNLA may not have time for complicated machinations. Until today it had seemed increasingly possible that the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) would send a peacekeeping detachment to Mali, though the contours and rules around an eventual deployment were never clear. Reports indicate that ECOWAS and the Malian junta reached a deal for Captain Amadou Sanogo to step aside in favor of an interim transitional government to be led by parliamentary speaker Diouncounda Traore. In return, ECOWAS will remove travel and trade sanctions put in place following the coup.

Regardless of what’s going on in the south, though, the north will likely remain unstable, and the MNLA must move quickly to reassert its position in northern Mali. If not, it may find itself shut out of the major power centers in the newly “liberated” Azawad, left to contend with an increasingly assertive and entrenched “desert fox.”