In this article the author addresses the prevailing narrative that Boko Haram carried out the kidnapping and executions of two Europeans in northern Nigeria yesterday. By taking all of the evidence into account, the involvement of Boko Haram is one of several possibilities and to immediately place the blame on this group could be playing into the hands of the terrorists.

By Jack Hamilton, 9 March, 2012

In May 2011 two European construction workers were kidnapped in Kebbi, north-west Nigeria. Yesterday both of these men were killed in a botched rescue mission in Sokoto, northern Nigeria. Despite some bold assertions by the British and Nigerian governments, what exactly happened to the 28 year old Englishman, Christopher McManus and the 47 year old Italian engineer, Franco Lamolinara, and who they were taken by remains unclear.

First of all, regardless of who was responsible for the kidnapping and the rescue mission, the deaths of these two men is a tragedy. The decision of the British Government to intervene in such a way must have had the primary objective of getting the hostages out alive. Whether they were executed by the hostage takers or they were victims of crossfire in the ‘seven hour shootout’, their deaths represent a disastrous failure of British intelligence.

Now we must turn to the evidence of what happened to Mr. McManus and Mr. Lamolinara. It is important that the narrative of ‘this was Boko Haram’ does not take hold as at this time it remains speculation. As we will see, it is tenuous speculation.

In a statement today, a Boko Haram spokesperson announced: “We have never taken anyone hostage. We always claim responsibility for our acts”. Boko Haram certainly have blood all over their hands but they also like to brag about it. The fact that they have not done so in this case is revealing.

Sequence of Events Leading up to March 8

While kidnappings are common in the Niger Delta region of the country, they are not frequent in northern Nigeria and unheard of in the case of Boko Haram. The kidnapping of the two Europeans was not accompanied by any ransom demand and the State Police Commissioner has reiterated that the terrorists never attempted to make contact with local security forces.

The kidnapping itself was amateurish for two reasons. Firstly they allowed for some of their victims to escape and secondly they left a bag of money behind.

Nothing was heard from the kidnappers of their victims until a video was released in August of last year. In this one-minute video the terrorists claim that they are members of al-Qaeda and show the hostages blindfolded and on their knees in front of their armed captors.

The video raises several possibilities. Using such a technique is characteristic of al-Qaeda, as the group claim to be, and would provide the first evidence that the group is operating on Nigerian soil. However, this does not mean that it was indeed al-Qaeda as there are several irregularities.

Firstly, the video did not come from the al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb broadcasting centre, al-Andalus. Seeing as the terrorists were so willing to prove that they are affiliated with al-Qaeda, it would make sense to go through the processes that the group tends to use. Sending an amateurish video to AFP in Abidjan does not fall within this process. AQIM tend to broadcast their kidnapping videos on jihadist websites with their al-Andalus watermark.

The second irregularity, pointed out by an expert on AQIM, Andrew Lebovich, is that they are not wearing the traditional attire of Salafis. No Salafi organisation, with the exception of al-Qaeda in Iraq, dresses in the casual way the terrorists present themselves in the video.

This opens up the possibility that the organisation in question wishes to be seen as AQIM or Boko Haram to increase their bargaining stance. Such a claim is pure speculation until the demands of the organisation are released but the lack of attention to detail is incongruous with the moniker they claim. If they turn out to be pretenders, the media coverage reporting on the ‘Boko Haram’ kidnapping has fed directly into their hands.

What Happened on 8 March, 2012?

Location

The location of the hostages in Sokoto is highly significant. If they had been taken to Kano or Maiduguri there would be little doubt that Boko Haram carried out the attacks. Reporting from top news sources, including Sky News, is incorrect in implying that Sokoto is a Boko Haram base.

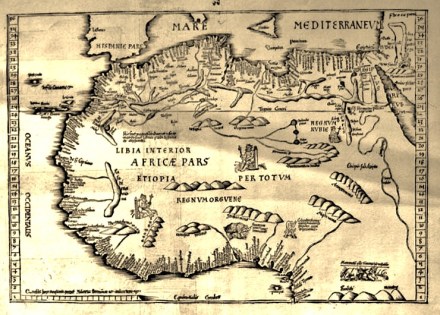

It is worth looking at Andrew Walker’s map of the instances of Boko Haram terrorism in comparison to the location of the Kebbi kidnapping and the shootout in Sokoto. The operations of the organisation have not come anywhere near this part of Nigeria.

This is not to excuse Boko Haram. There are two ominous possibilities. Firstly, that Boko Haram has significantly expanded its geographical reach across Nigeria and has begun to undertake tactics that resemble those of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. Secondly, that there are now two of these groups in Nigeria.

What was the reason for the sudden raid?

The Foreign Office has reported that they received intelligence saying that the hostages were about to be executed or moved. This has been taken further by an article in The Guardian stating that the intelligence came following the arrest of a top Boko Haram official in Kaduna, northern Nigeria. It also credits the British intelligence forces for training the Nigerian officials who were able to uncover this crucial information. It remains unclear whether the arrest of these men in Kaduna was the trigger for the execution of the hostages.

For such a decision to have been taken it is clear that the lives of the men were in imminent danger. A factor emphasised by David Cameron in his apologetic speech yesterday afternoon.

Cameron gave the go-ahead following meetings of the government emergency committee, Cobra. The Italian Prime Minister, Mario Monti, was only made aware of the rescue operation after it had begun. He was informed that “an unpredicted acceleration of events took place over the last hours. While fearing an imminent danger for the hostages, Nigerian authorities activated the rescue” by Cameron.

Various Italian MPs have demanded clarification for why Monti was not alerted earlier but this is not the big story. It is clear that it was a rushed rescue operation conducted on a short time scale. It is highly unlikely that the wisdom of the Italian Parliament, no matter how well versed they all were on the intricate security politics of north-western Nigeria, could have remedied this situation.

The events of the raid on the compound yesterday remain sketchy, hence the Italian demands for clarity on exactly what happened and why they were consulted so late in the day.

There are conflicting stories of how events unfolded. The BBC states that “the British were the first at the door” while local sources, such as The World Today, state that the Nigerian state forces used a tank to break down the wall of the compound where the terrorists were holed up. The lack of coherent information is most likely a result of journalists being kept one kilometre away from the shootout.

Sahara Reporters have released pictures of the compound after the attack. WARNING: some of the pictures contain spatters of blood on the walls. [pictures]

It is unclear how it came to be that the two hostages were killed but most sources agree that they were whisked deep inside of the compound as soon as the raid began and executed them immediately. This would imply that the intervention had little chance of success to begin with if true. It begs the question: why did foreign forces get involved?

The intervention of British forces on Nigerian soil seems now like a strange decision to have taken. It is a clear sign that Britain did not trust the Nigerian forces, who they themselves had trained, to carry out the operation. Instead it was led by the Special Boat Squadron (SBS) including Royal Marines in a mission which may have numbered twenty British personnel.

The Role of Nigerian State

Nigerian intelligence, according to President Goodluck Jonathan, has arrived at the definite conclusion that Boko Haram were behind the kidnappings and the attack. This claim must be taken with a pinch of salt given the recent record of Nigerian intelligence, especially in dealing with Boko Haram. It is in the interests of the Nigerian state to put forward a message that they are taking control of the deteriorating security situation in northern Nigeria.

If the narrative of the tragedy takes the form of ‘Nigerian forces kill eight members of Boko Haram following intelligence success’, it will reflect well. If this was not Boko Haram, the intelligence reports from Kaduna must be looked at again to see if the tragedy was a result of a Nigerian intelligence failure. For many in the north of Nigeria, the success and popularity of Boko Haram is down to the failings of the Nigerian State’s security.

Did the Terrorists Win?

The demands of the terrorists have not been stated. If the intelligence reports from Kaduna are to be believed there must have been some hint at the ambitions of the organisation when these men were revealing the location of the hostages to the security services. It has been reported that in the initial kidnapping, a large bag of money was left behind. Perhaps the perpetrators believed that the ransom payout would be swift and bountiful. Perhaps the kidnapping was for political rather than economic motivations. To state a case for either based upon the bag of money would be pure speculation. It is therefore more useful to look at the previous actions of Boko Haram to see if the terrorists were following a pattern.

The kidnapping of foreign nationals does not fit with the previous actions of Boko Haram. Their demands have tended to be on religious institutions and local government with little violence reserved for international bodies (with the exception of the bombing of the UN in Abuja). If the desire was, as with the UN, to gain international attention, the actions of British and Nigerian intelligence played straight into their hands by attempting what would be a futile rescue operation if it was carried out by Boko Haram. The organisation could undoubtedly gain more attention from killing the hostages which begs the question: if British intelligence sources truly believe the aggressors to be Boko Haram, why did they play straight into their hands?

Below is my interview on Sky News as the news broke