In this article, the author assesses the success rate of how oil-rich countries in the Arabian peninsula and beyond have tackled the challenge of increased oil revenues and how they have handled their newly established wealth. For many, oil has been a curse in disguise, with mismanagement of oil revenues, unequal distribution of wealth and the Machiavellian power of the rentier state – which in the case of Libya proved to be fatal.

By Matthias Pauwels, 26 Oct, 2011

Roughly a century ago, nobody would have imagined that a complex mixture of hydrocarbons of various molecular weights and other liquid organic compounds would become the most contested, sought-after commodity in the world. Oil-rich countries in the Middle East have been the scene of epic battlegrounds to gain control over the black gold. As a crafty tool to conduct psychological warfare, petrodiplomacy has become an important diplomatic weapon to the Arab nations against the West and, in particular, Israel. When crude oil found its way to the international market during World War II, the world became increasingly dependent on Arab oil. For over half a century, the oil industry of the world outside North America and the Soviet Union had been dominated by seven great international oil companies, exercising control over output and off-take prices. However, the tide was turning. By the 1960s-1970s control over Middle Eastern oil was rapidly passing into the hands of governments in the area and out of the hands of the heretofore dominant Western companies. International oil companies, once the beneficiaries of lucrative concessions and tax arrangements, slowly lost the control they traditionally exercised over Middle East oil production and pricing and had to accept policies determined unilaterally by the producing nations.

Consequently, a sudden increase in the rate of revenue flows to the Middle East simultaneously presented the economic planners of the region with an unprecedented opportunity and challenge. Over the past decades, very large increases in the revenues accruing to the oil-exporting countries have given rise to extravagant hopes of a swift acceleration in their economic development.

At the dawn of the twenty-first century, we are able to assess the success rate of how these countries have tackled the challenge of increased oil revenues and how they have handled their newly established wealth. Here I am arguing that for countries of the Arabian peninsula, oil, paradoxically, is a curse in disguise. Although the possibilities of oil revenue flows appeared unbridled, these governments have largely crumbled under the huge pressure to properly utilise this wealth.

Firstly, the mismanagement of large proportions of oil revenues is embedded in the asymmetry of economic, political, and cultural perspectives. Practices such as unwise spending policies and loose budgetary controls have produced the caricature – so popular in the West – of the rich Arab with dark glasses and his Rolls Royce. Secondly, unequal leaps of development in the Middle East, often based on oil revenues, have accentuated multilateral social and economic inequalities. As a result, Pan-Arabism has declined. Thirdly, the sole concentration on oil revenues has proved to be a slippery slope: declining oil revenues in an undiversified economy leave young people with reduced changes and disappointment, creating a breeding ground for Islamism to firmly nestle itself in the consciousness of the common Arab youth. And finally, the most desirable course for relations between consumers and producers of oil remains the issue of heated argument. Over the past decades, the world has witnessed several oil crises, the establishment of OPEC and severe fluctuations in oil prices, directly affecting the world economy. Rather than moderating with time, the debate of optimising the relationship between consumers and producers of oil remains volatile.

1. The paradox of oil: a financial curse in disguise

The actual utilisation of oil as a strategic commodity of great political potency as well as developmental power has left the Middle East faced with numerous challenges. When Saudi Arabia imposed the first income tax on oil companies in 1950, the law was specifically designed to capture fifty percent of the profits attributed to crude oil. As a result of these arrangements, the revenues of oil-producing countries of the Arabian peninsula soared, and their governments seemed satisfied. As time moved on, a final transfer of power of petroleum from companies to governments in the 1973-1974 period created the opportunity to fully gain control over oil revenues. Although there was a realisation that oil resources of the region would ultimately be depletable and the development of more diversified domestic economies, capable of generating their own funds for investment, should be made a “first priority goal”, the Middle East has received considerable criticism for the way they have handled their new wealth. In this context, authors such as Sayigh allude to the misdirection of an inordinately large proportion of oil revenues into the private accounts of rulers, continuing wastefulness, loose budgetary controls and unwise spending policies which permitted overconsumption and the formation of private “princely fortunes” in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the Gulf sheikhdoms.

It is certainly true that the construction of superhighways and the building of stadiums that will only be filled sporadically fully testify to the folly of oil revenue investments. The real estate investment bubble of Dubai has burst, a process which was accelerated by the financial crisis of 2008. Additionally, Qatar has recently invested an unprecedented oil revenue budget in bringing the World Championship Football to the small Arab emirate in 2022.

Although many do not deny the existence of the concept of “conspicuous investment”, one can argue that the comic, Orientalist figure of the wealthy oil sheikh, with his thousand-and-one night palaces and lavish cars, has disappeared. In this context, Sayigh notes that after a few years of wasteful confusion in the oil countries, careful procedures were developed for assigning revenues to capital and current expenditures. Huge infrastructural projects have been undertaken in transport, communications, power, irrigation, land reclamation, housing, urban facilities, education and health – all of which have helped to consolidate the economic base.

While I do not contest that attempts have been made to create more diversified domestic economies in the realisation that oil resources may ultimately be depletable and to cope with the changing panorama of energy sources, Sayigh’s observation should by no means be generalised. Although efforts have been made by governments to sensibly manage the impressive flow of oil revenues, problems of misspending, overspending and overconsumption are not a manifestation of the past. True, Kuwait has been blazing a trail for sensible domestic oil revenue investment through the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development (KFAED). During the past three decades, the country has more or less found a balance in allocating equal portions of its income to three areas: domestic development, regional development and foreign investment. Dubai, on the other hand, has played the role of the golden child of the Emirates for the past two decades, massively investing in urban development, the expansion of industry, infrastructure, and the modernisation of transportation. The government’s decision to diversify from a trade-based, oil-reliant economy to one that is service and tourism-orientated has made property more valuable. A longer-term assessment of Dubai’s property market, however, showed depreciation. Some properties lost as much as 64% of their value from 2001 to November 2008.

Dubai’s property market experienced a major downturn in 2008 and 2009 as a result of the slowing economic climate and when by early 2009 the situation had worsened due to the global economic crisis, the emirate was faced with an $80 billion debt due to overspending, and was forced to seek financial help from other emirates. Although Dubai’s intentions are noble to invest in creating a diversified economy, not solely reliant on oil, unwise spending policies are not a manifestation of the past.

2. Political consequences of the oil effect

Aside from the financial challenges oil extraction has brought countries of the Arabian peninsula, one can put this in the perspective of two extremes: on one hand, the Arab oil states have enjoyed stability, continuity and wealth to a degree unknown since the 1950s. On the other hand, the glaringly uneven distribution of resources among the various sectors of the population has provoked anger and frustration. Furthermore the rising social status and self-awareness of the middle class and its low political status, combined with unemployment, has created a breeding ground for Islamism, although there is by no means an exclusive link between oil exports and the rise of militant Islam.

The one significant political development noticeable during the oil decade is the decline of the ideal of Arab unity and Pan-Arab solidarity. Since the 1950s, Pan-Arabism is on the decline, with the occasional flicker of revival during the Arab-Israeli conflict. In general, revenues from oil have exacerbated the differences in the economic conditions of the Arab states, particularly between the sparsely inhabited oil states of the Arabian peninsula and the densely populated countries of the Nile Valley.

By the late 1970s, a deepening economic gap had opened between the populations on either side of the Red Sea – that of the Nile Valley and that of the Arabian Peninsula. Its impact was considerable, and meant among other things a weakening of the forces calling for Arab unity while it favoured the territorial Arab nation-states. In addition, the failure of Nasserism and its view on Pan-Arabism weakened Egypt’s ideological opposition to the existence of separate Arab states. Unwillingly, Egypt was forced to turn to Arab oil producers for aid.

However, the decline of Pan-Arabism is no exclusive international phenomenon. Even domestically it can be disruptive to a harmonious feeling of unity. Despite the United Arab Emirates’ increased sharing of the oil wealth with the poorer, non-oil sheikhdoms through the confederation government, the contrasts in wealth have continued to underscore the urgent hope of the have-not rulers of Ajman, Fujayrah, Ra’s al-Khaymah, and Umm al-Qaywayn that it would be only a matter of time before they, too, became oil producers. Alledgedly these contrasts have been the root of many political differences between the rulers. In this light, the hope that an oil discovery on its territory was imminent was the main reason for Ra’s al-Khaymah to delay joining the U.A.E. until February 1972. And so, oil and the hope of prospective oil wealth became an obstacle for Pan-Arabism, both internationally and domestically.

3. Oil and Islam: a breeding ground for political polarisation?

Islamism today is a universal phenomenon in the Muslim world. Therefore the mere hypothesis of a strict connection between oil and Islamism is too far-fetched. It is by no means an exclusive phenomenon of oil exporting countries. Even the study of potential links between oil exports and the rise of Islam remains empirically difficult.

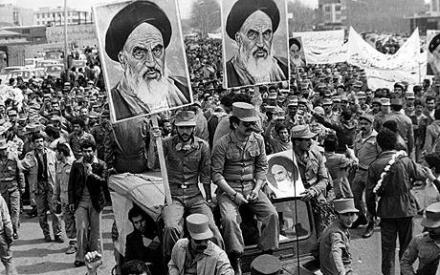

When we do shine a light on Islamist movements in oil exporting countries, it becomes clear that they represent both a social revolt as well as an assertion of cultural and national identity in the wake of an unsuccessful or incomplete modernisation based on oil. Rapid population growth, immature and unstructured political systems where ageing leaders stay in power without accountability to the public, and the autocratic nature of these political systems have been known to create social and generational tensions. Many Muslim countries have old rulers, who control the government and have a firm grip on the economic surplus. Often they also tend to represent Western ideas and lifestyles to a considerable extent. Opposition to them is a frustrated middle generation and especially an impoverished, unemployed youth – no surprise there in context of the recent Arab Spring. They want influence, prosperity and to assert cultural traditions against Western influence. Such a stereotype may be particularly relevant to the oil exporting Muslim countries. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States, the United Arab Emirates was identified as a major financial center used by al-Qaeda in transferring money to the hijackers. Moreover, two of the 9/11 hijackers who were part of the group that crashed United Flight 175 into the South Tower of the World Trade Center, were UAE citizens.

Unequal leaps of development in the Middle East, often based on oil revenues, have accentuated social and economic inequalities, as I have mentioned earlier. The issue here can be described as being three-fold: it is social, concerning the distribution of income, wealth and power; cultural and national, concerning political and personal identity; and generational, affecting conflicts of power between age groups with different experiences and expectations.

However, oil exports appear to be neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for the rise of Islamism. If they were a necessary condition, Islamism would not have been present in non-exporting oil countries such as Sudan, Lebanon or Palestine. If they were a sufficient condition, oil exports alone would have provoked a strong surge of Islamism in, for instance, Kuwait. When it comes to the 9/11 hijackers, it probably was a mere coincidence that both men had the UAE nationality, although al-Qaeda has been known to frown upon the “ emerati wastefulness” and splurging lifestyle. But a direct causal link between oil exports and Islamism would be indirect and highly complex. As an alternative, authors such as Noreng suggest three sensible reasons for possible links between oil and Islamism. First of all, when oil revenues decline, the public sector suffers from diminishing resources and a frustrated private sector emerges. Secondly, declining oil revenues in an undiversified economy leave young people with reduced changes and disappointment. And thirdly, there is a ripple effect from the oil exporters to the non-oil exporters. When oil revenues rise, the rich oil exporters employ labour from the non-oil exporting countries of the region. They in turn remit money home and increase the GNP of their home country. When oil revenues decline, foreign workers lose jobs, go home and remittances diminish. This way, religion creates an escape and an outlet for frustrations. It is however important to mention that the sole combination of misery and mosques does not by itself produce Islamist movements. Islam’s social promise has to be elaborated, interpreted and presented by a conscious elite able to influence the masses and propagate Islamism to the people.

The social task of Islam focuses precisely on an equal distribution of wealth through the zakat, the wealth tax, which has become an imperative duty for devout Muslims. The specific purpose of the wealth tax is to prevent the rise of any rentier class in the economic system. The specific problem of oil is that it creates an influx of rentier income. Oil provides much money without much effort. In a Middle Eastern context, oil seems to have produced a special political system, based on the centralisation of petroleum revenues within the state. Here, the state is the distributor of economic rent and favours instead of being a tax collector and redistributor. Rulers tend to hand out selective privileges, financed by oil revenues, against loyalty and support from a large private sector. This way, political loyalty is exchanged for economic favours. This is the basis of a classic rentier state. Islamic economic principles can be used to fight or prevent the rise of a rentier class within a state. The problem with oil revenues for Islam is that they differ qualitatively from productive income, because they have their origin in the extraction of a finite resource, not in human labour and productivity: it is “easy” money. When wasteful consumption above reasonable needs goes hand in hand with mismanagement of income distribution and wealth, Islamism may once again find a breeding ground in these rentier states, drawing back upon Islamic economic principles, such as the zakat.

4. What role has oil played in the Libyan crisis?

Libya’s petroleum sector has been critical in shaping its political economy. Although Libya ranks 17th among global oil exporters, its 46.4 billion proven oil reserves are the largest in Africa – practically the size of Nigeria and Algeria combined. Over the decades this sector has provided significant resource inflows for Gaddafi. Oil revenues laid the foundation for the establishment of the Libyan rentier state, where rents from natural resources rather than domestic productivity were the backbone for economic growth. The rentier state in Libya was responsible for mass unemployment and poverty since the vast majority of Libyans without access to oil rents hardly benefitted from the country’s wealth, while Gaddafi and his cronies distributed oil wealth via a highly exclusive patronage network and the “republic of the people” effectively eviscerated opposition politicians.

As the dominoes started falling across North Africa, it was only a matter of time before unrest spilled over in Libya. However, Libya was different from Tunisia and Egypt. Without a history of opposition activity, the rebellion has been poorly coordinated and clear leaders were hard to identify. The patronage system appeared to be strong and those benefitting from Gaddafi’s largesse were quick to rally to his side in the initial stages. Moreover, Libya’s patronage system was highly liquid, as evidenced by the more than $60 billion government deposits in local banks – an astounding 99% of Libya’s GDP. By comparison, lending to the private sector only accounted for 11% of its GDP, underlying the rentier characteristics of Libya’s political economy.

5. Arab petrodiplomacy: a double-edged weapon

The concept of oil as a diplomatic weapon and means for psychological warfare is as old as the Arab-Israeli conflict itself. Especially during the 1967 six-day Arab-Israeli war, Middle East oil became even more important as a diplomatic weapon to the oil-exporting Arab nations due to the fact that oil had almost entirely replaced the use of coal since 1965. However, the use of oil as a diplomatic weapon by the Arab nations against the West has its pitfalls. Applying diplomatic pressure through oil embargoes has mainly missed its primary target, since the United States has remained virtually unaffected by them. Before the oil weapon could cause irreparable damage to the American economy in the 1973 oil crisis, the oil embargo was quickly eased. The early lifting of the embargo was driven by economic impulses that a major recession in America would affect the entire world adversely. Moreover, the oil embargo of 1973 has paradoxically strengthened the American position in the Middle East, especially in Saudi Arabia. American oil companies, such as Aramco, are still making high profits and continue to operate in the region.

6. Conclusion

Whether we are discussing the pitfalls of Arab petrodiplomacy, the intricate task of sensibly managing oil revenues, the dangers of becoming a breeding ground for Islamist groups or the rise of the rentier state, oil-rich nations of the Arabian peninsula and beyond have been confronted with numerous challenges. Although the possibilities oil and its revenues can provide seem endless, they are nothing but a curse in disguise. There are still huge challenges to face when it comes to creating sensible spending policies, managing budgetary controls, keeping overconsumption in check but above all, an equal distribution of wealth. Still too often oil revenues are used solely to aggrandise private fortunes. More efforts should be made to create diversified economies, expand the private sector and ensure that oil revenues are reinvested in domestic development programmes. Development, to mean anything at all, must include the development of the productive capacities of the people themselves, and this is only partly promoted by the provision of transport facilities, factories, buildings and other infrastructure. The receipt of foreign revenues – money – does not in itself improve the capacities of people, a common mistake which oil-rich Middle Eastern countries have often made. This is what we can call absorptive capacity: beyond a certain level, no increase in the availability of capital or other direct inputs can influence the rate of development if a country lacks the social, institutional, and political capacities to utilise increased capital, labour, and natural resources.

References

- Ali, Sheikh R., 1987. Oil and Power: Political Dynamics in the Middle East. London: Pinter Publishers

- Anthony, John Duke, 1975. The Impact of Oil on Political and Socioeconomic Change in the United Arab Emirates. In J.D. Anthony, ed. 1975. The Middle East: Oil, Politics and Development. Washington: American Enterprise Institute for Policy Research, Ch. 4.

- Armitstead, Louise, 2008. Dubai’s Palm Jumeirah sees prices fall as crunch moves in. London: The Daily Telegraph (20 November 2008).

- Gilbar, Gad G., 1997. The Middle East Oil Decade and Beyond: Essays in Political Economy. London: Frank Cass & Co LTD.

- Licklider, Roy, 1988. The Oil Weapon in Theoretical Context. In R. Licklider, ed. 1988. Political Power and the Arab Oil Weapon. London: University of California Press, Ch. 1

- Licklider, Roy, 1988. The “Lessons” of the Oil Weapon for Theory and Policy. In R. Licklider, ed. 1988. Political Power and the Arab Oil Weapon. London: University of California Press, Ch. 7

- Loutfi, Muhammed, 1975. Prospects for Development and Investment For Oil Producing Countries. In J.D. Anthony, ed. 1975. The Middle East: Oil, Politics and Development. Washington: American Enterprise Institute for Policy Research, Ch. 4.

- Noreng, Øystein, 1997. Oil and Islam: Social and Economic Issues. Chichester, West Sussex (UK): John Wiley & Sons LTD

- Penrose, Edith, 1975. International Oil Companies and Governments in the Middle East. In J.D. Anthony, ed. 1975. The Middle East: Oil, Politics and Development. Washington: American Enterprise Institute for Policy Research, Ch. 1.

- Said Zahlan, Rosemarie, 1999. The Making of Modern Gulf States: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Oman. New York: Ithaca Press

- Sayigh, Yusif A., 1975. Oil in Arab Developmental and Political Strategy: an Arab View. In J.D. Anthony, ed. 1975. The Middle East: Oil, Politics and Development. Washington: American Enterprise Institute for Policy Research, Ch. 2.

- Stocking, George W., 1970. The Economics of Middle East Oil Pricing: Costs, Prices, Profits and Revenues. In G.W. Stocking, 1970. Middle East Oil. Tennessee: Kingsport Press, Inc., Ch. 21

- Tempest, Paul, 1993. The Politics of Middle East Oil. London: Graham & Trotman Limited