In this article, Paul Ingram* argues it is time to reframe debates on the Iranian nuclear programme. If we want to solve the current impasse, we need to move from a pervasive rhetoric based on security threats and mutual accusations to a cooperative framework more apt for negotiations.

In this article, Paul Ingram* argues it is time to reframe debates on the Iranian nuclear programme. If we want to solve the current impasse, we need to move from a pervasive rhetoric based on security threats and mutual accusations to a cooperative framework more apt for negotiations.

By Paul Ingram, 25th April, 2012

All too often the story around the Iranian nuclear issue is framed as our effort to contain the wild ambitions of a delinquent revolutionary state that with nuclear weapons given half a chance will threaten the stability of the world. This frame sticks for two key reasons: firstly because it plays into some of our greatest fears, and second, because there is enough of a hint of truth to it that people forget the qualifications, the underlying causes and the contrary evidence. In short, we fail in the face of complexity to understand the challenge, and the role of both sides in creating it. And in fact, many of the accusations made against Iran are mirrored in Tehran in things said about the West.

Western intelligence agencies continue to confirm that there is no strong evidence to back up the claim that Iran is engaged in a technical sprint to fulfil an ‘ambition to attain nukes’. Postulating reasons why Iran might want such capabilities is all very well, but such approaches are fraught with analytical and cultural traps. There are equally persuasive explanations for Iran’s programme that it would be equally dangerous to depend upon, such as the idea that Iran is caught up in an effort to demonstrate its modernity through the development of cutting-edge technologies, or that it is pursuing an energy-mix that both brings in foreign exchange and provides for an ever-increasing energy-hungry economy. The truth probably includes a balance of many explanations, including the fact that its technology development gives the administration a future option for nuclear deployment that may be seen as valuable in itself.

The talks in Istanbul last weekend between the E3+3 and Iran were best summed up by Guardian journalist Julian Borger ↑ as a play for a score draw, at least for now. Emerging without recriminations was in itself an achievement. But of course the challenge is how we get beyond this to reaching more substantive agreement in Baghdad on 23 May, when there have been so many factors in the way. Over the coming months, Iran faces some pretty severe additional sanctions, on top of crippling ones recently imposed. When previously people may have accused them of playing for time this is no longer be the case. In fact if anything it was Catherine Ashton↑, lacking a mandate, who last Saturday was playing for time when Jalili was looking for a deal that would soften impending sanctions. The best way of securing stocks of material in Iran is by negotiating access, not by threats, which only provide Iran an incentive to continue. Israeli protests over Iran’s increasing ‘immunity’ to attack ignores the fact that Iran has every right to protect themselves against illegal military threats. As Peter Jenkins↑, former UK Ambassador to the IAEA puts it, Iran bought itself immunity from attack by being a member of the United Nations and a signed up member of the NPT. Israeli military threats only make it more difficult for Iranian politicians and diplomats to sell any deal to their constituents.

There are plenty of frameworks out there to negotiate on that take the parties step-by-step in the direction of a technical agreements whilst the underlying trust essential to lasting improvement can be built up. Indeed, this is the only approach that holds any promise of working in negotiations. It will require parties to drop preconditions and talk with a view to understanding the other side’s perspective. Each step will need to involve net gains for both sides, as well as a clear sense of where the process is going. There will need to be maximum exploitation of common interests in other security areas – such as counter-terrorism and counter-narcotics activities. Positive signals such as those given recently by both President Obama and Ayatollah Khameini will need reflection, and negative, hostile rhetoric scaled back.

But we will also, in parallel have to tackle some of the deep-seated fears and attitudes that prevent progress. One such on the western side is a deep-seated exceptionalism around sovereignty that pervades the majority view. How much do we all share the attitude that we have a right to demand unlimited access and control over others’ nuclear programmes whenever we have our own suspicions? We have every reason to develop international systems based upon agreement and universal application, but we cannot force others into agreements, and certainly not those we are not willing to submit ourselves to. As a nuclear weapon state Britain is unwilling to seriously consider abandoning the highly expensive practice of keeping a nuclear submarine at sea at all times, or to share such a practice with France, for example, because we have such a powerful attachment to the concept of British sovereignty based upon the ability to threaten massive retaliation against any other state on the planet. This is bound to drive proliferation, sooner or later. Regionally, the inconsistent focus on Iran without any clear plan to address Israeli possession of a nuclear arsenal cannot be justified by a legalistic appeal to Israel’s non-membership of the NPT. As non-signatories the Israelis may not be directly breaking the law, but if we are to claim that the health of the international community depends upon a strong ethic of non-proliferation, then Israel cannot remain an out-law.

We cannot continue to have partial approaches to dangerous technologies. Did you know that India’s successful missile test this week broke a UN Security Council resolution, just as North Korea’s failed one last week did? Few have reported it.

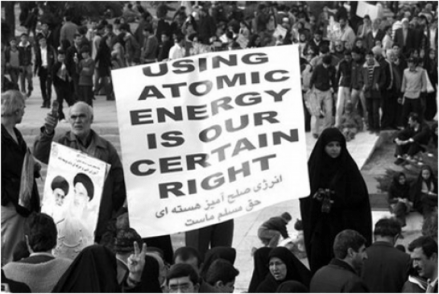

On the Iranian side, it’s time they evolved the rather male pig-headed pride so ably illustrated in last year’s prize-winning film ‘the Separation’, an approach that too often characterises (though not uniquely) Iranian diplomacy and politics. Standing on one’s rights or maintaining an inflexible position can harm one’s own interests in fundamental ways, and destroy one’s position within the community, international or otherwise. International communities require trust, empathy and reassurance. They also depend upon a level of transparency and responsibility. Iranians have to recognise that for a variety of reasons they have a long way to go to build the trust of their neighbours, the sort of trust that will enable them to overcome the isolation they have suffered, isolation that threatens to deepen as the Syrian government goes down and their allies in Lebanon and the Occupied Territories start to look elsewhere for sponsorship in the context of the Arab Spring.

But the deeper choices lie in the international community’s relationship to nuclear deterrence, and how power has in the past been mediated by possession of nuclear arsenals. If we cannot break free from Cold War theologies that place such magical powers in the possession of nuclear weapons, we will only have ourselves to blame when the weapons spread, and those we fear most acquire the magic we have sought to invoke in defence of our privileged positions.

The views expressed in this article solely reflect Paul Ingram’s personal perspective.

____________________________________________________________________________________

*About the author: Paul Ingram is Executive Director of the British American Security Information Council (BASIC) where he develops BASIC’s long-term strategy to help reduce global nuclear dangers through disarmament and collaborative non-proliferation, coordinating operations in London and Washington. He is also a weekly talk-show host on Iranian TV. This article was first published in Open Democracy on 23 April 2012 (the original article can be accessed here).