In this paper, the author analyses the motivation, framework and the socio-economic impact of India’s Special Economic Zones (SEZ) Act of 2005.

In this paper, the author analyses the motivation, framework and the socio-economic impact of India’s Special Economic Zones (SEZ) Act of 2005.

By Siddharth Singh, 16 Oct, 2011

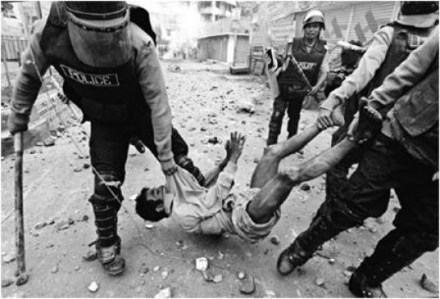

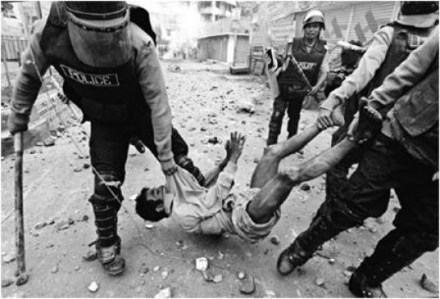

Special Economic Zones (SEZs) have been touted to be magic pills for nations to kick-start exports, develop infrastructure, and increase employment by adhering to the principles of free markets and minimum distortions caused by effective administration and low or no taxes (Tantri, 2010, p26). Owing to the success of China and other countries, India took up the development SEZs with much enthusiasm, but the outcome has not entirely been as desired. On the one hand, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry reports impressive figures to show how SEZs have “worked” (discussed below), but on the other hand, there are cases such as that of Nandigram, West Bengal (The Telegraph, 2007) where 14 people died in March, 2007 while protesting against the establishment of a chemicals hub SEZ by an Indonesian developer (Manoj, 2009, p355 and Dohrmann, 2008, p75).

In an attempt to understand India’s experience with SEZs, this essay will first look into the motivations of setting up SEZs. It will then assess the framework the SEZ Act of 2005, and finally, move on to scrutinise the social and economic impact of this policy.

The Rationale of the SEZ

An SEZ is a geographically delimited area administered by a single body, offering a certain incentive regime to businesses which physically locate within the zone (The World Bank Group, 2008, p2). An Export Processing Zone (EPZ) is a type of SEZ which is legally defined as a “policy enclave” within the host state territory, to which distinct regime of custom and trade regulations apply (Muchlinski, 2007, p226). These policy enclaves are instruments to realise micro and macro-economic, and political objectives. Microeconomic issues include employment generation, while political objectives include implementing regional economic development strategies (Guangwen, 2003, p20).

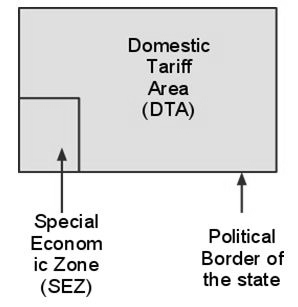

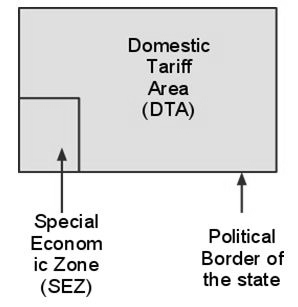

The SEZ is a subset within the geographical boundaries of the state. The rest of the host state is legally referred to as the Domestic Tariff Area or the DTA (Muchlinski, 2007, p229). Effectively, the SEZ is “outside” the territory of the host state with respect to trade and investment. Figure 1 below explains this relationship.

Figure 1

The host states can expect inter alia to earn increased export earnings, benefit from increased employment opportunities, improved training and skills, and transfer of modern technology (Muchlinski, 2007, p227). In return, foreign investors are offered incentives such as tax exemptions, duty free imports, exemptions from import quotas, capital mobility to remit profits, export allowances and subsidised interest rates within the SEZ. A significant incentive offered by the host state involves the legal control of labour relations. Specifically, the right to establish trade unions or take industrial action may be limited within the SEZ (Muchlinski, 2007, p229).

Political and economic stability, reliable infrastructure, inexpensive labour, market access, and efficient bureaucracy are factors that determine not only how attractive investors will find the SEZ, but are factors that eventually determine the success of the SEZ (UNIDO, n.d., p27).

Keeping in mind these objectives and demands, India embarked on a journey to use SEZs as engines of economic growth. India set up Asia’s first EPZ set up in Kandla in 1965. The government announced the SEZ policy in April 2000, claiming to “to overcome the shortcomings experienced on account of the multiplicity of controls and clearances; absence of world-class infrastructure, and an unstable fiscal regime and with a view to attract larger foreign investments in India” (SEZ India, 2011a, Introduction). The Foreign Trade Policy provisions governed SEZs in India prior to the implementation of the SEZ Act, 2005 in February, 2006 (Chandrasekhar and Ghosh, 2007).

Salient Features of the SEZ Act (2005)

‘The Special Economic Zones Act, 2005’ was passed on the 23rd June, 2005, in an attempt to give a framework to the implementation of SEZs in India. It includes several regulatory and investment fostering mechanisms.

i. Creation of SEZs and general administration:

The Act explicitly mentions a few guiding principles for the Central Government regarding the creation of SEZs. The objectives of the government, as stated by the Act, must be to generate additional economic activity, promote exports of goods and services, create employment opportunities, and develop infrastructure, all while maintaining the “sovereignty and integrity” of India

(SEZ Act, 2005, p8). Thus, SEZs have thus come to be justified as an engine of growth and employment generation, and not in terms of exports expansion alone (Sharma, 2009, p18).

The Act calls for the creation of the “Board of Approval”, which, as the name suggests, looks into applications to set up SEZs and gives approval to them if they meet the required criteria. This acts as a single-stop-shop for investors (called ‘developers’) to get the required regulatory permission to set up an SEZ. SEZs may be established under this Act either jointly or severally by the Central Government, State Government of any legal person. The Central Government, however, can suo moto set up SEZs, and can prescribe other requirements at a later stage (SEZ Act, 2005, p1-6).

The position of a Development Commissioner is established (p14), and this position is responsible for the general overview of the SEZ, from presiding over the Approval Committee (p17-18) to running the SEZ Authority, which is in charge of provision of infrastructure, promoting exports. reviewing the functioning and performance of the SEZ, and other such functions (p28-29).

ii. Tax Exemptions, Finance and Banking

By definition, SEZs are so-called “tax havens”. The Act specifies all those taxes and duties that the developers would be exempted from in the SEZs. There is exemption from Custom Tariff Act, 1975, Central Excise Act, 1944, Central Excise Tariff Act, 1985 and other similar laws (p24). 100% Income Tax exemption on export income for the first 5 years, and 50% for the next 5 years is offered (SEZ India, 2011a, Facilities and Incentives).

Attention is also given to the trade between the SEZ and the DTA. The Act (SEZ Act, 2005, p8) prescribes the exemption from the payment of duties, taxes or cess under all enactments of the First Schedule for trade between DTA to SEZ. However, any goods moved from the SEZ to the DTA would be subject to safeguarding duties, anti-dumping regulations and other instruments (p26).

The Act also specifies the financial governance structure of the SEZ. Bank branches in SEZs, for example, are defined as ‘Offshore Banking Units’ (SEZ Act, 2005, p3-4), and can be set up after the approval of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), which is India’s central bank (p20). Other financial activities in the SEZ would be monitored by the relevant regulatory authorities in the DTA (p21).

iii. Law Enforcement

Were illegal activities to take place, the Act states that the Development Commissioner would have the cases investigated, and the cases would be heard at the court(s) appointed by the State Government and the Chief Justice of the state High Court (SEZ Act, 2005, p22). The Act also explicitly states that in case there is any inconsistency of this law with other laws, than this Act would have an overriding effect over others (p34).

iv. Amendments

Over the years, several amendments have been made to the Act. They have primarily revolved around specifying the provision of infrastructure and requirements for establishment of SEZs. The minimum area requirements vary across industries and regions. As an example, a multi-product SEZ has to be between 1000 and 5000 hectares, and at least 50% of the area needs to be earmarked for developing the processing area (SEZ India, 2010, ch II sec. 5, sub-sec 2 a).

Amendments also allow for the generation, transmission and distribution of power within an SEZ (sec. 5, sub-sec 5 c). Importantly, in the case of an information technology related SEZ, 24 hours of uninterrupted power supply is to be provided, apart from reliable connectivity (sec. 5, sub-sec 5A).

Importantly, a stated objective is the generation of positive net foreign exchange earnings, as it is specified that a unit would achieve positive net foreign exchange, calculated cumulatively for a period of five years from production (ch VI sec 53).

The Act is clear in specifying the framework regarding the implementation of an SEZ promotion strategy. The Act however, remains conspicuous in its silence on land acquisition and labour laws, which has become the bone of contention on the implementation of the policy.

A Brief Overview of SEZs in India

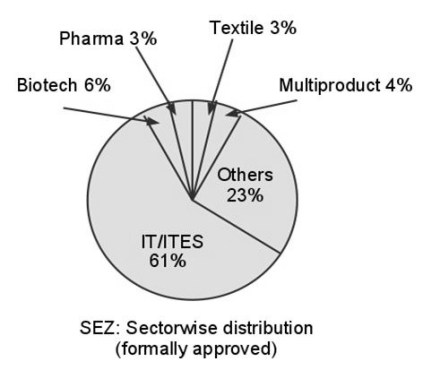

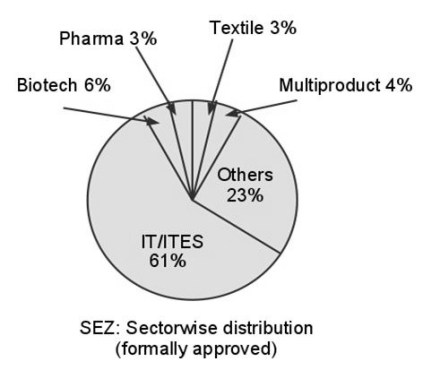

Prior to the enactment of the SEZ Act, 2005, there were 19 SEZs across India. The government has now approved 581 SEZs (SEZ India, 2011b) with a further 154 with in-principle approvals (SEZ India, 2011c). 130 of these SEZs are operational today. 283 of the 581 approved SEZs are in the three states if Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu (SEZ India, 2011d). Of the sectors, the Information Technology and IT enabled services sector has a 61% share of SEZs, while the biotech, pharma, textile sector and multi-product SEZs have less than 10% share each. Apart from these, there are three airport based multi-product, and eight port-based multi-product SEZs (SEZ India, 2011e).

Source: SEZ India, 2011e

The Indian experience in the implementation of SEZs has brought to light major areas of concern in the economic and social spheres. In the economic sphere, these are related to fiscal costs, net employment generation and exports. The social experience of SEZs has brought up issues of worker rights, and those of land transfer, dispossession and displacement. The next two sections of the paper will look into these briefly.

The Economic Experience

i Fiscal issues and investment:

Tax holidays in the SEZ are generous, and provide 100% exemption for Income Tax on profits for the first 5 years of production and 50% for the next five years, apart from the tax breaks discussed above. In addition to this, land is given by the government to developers at low rates (Dutta, 2009, p23). Estimates by the Finance Ministry show that the losses to the state exchequer in terms of forgone revenue would be £24billion for an investment of £50billion (Chandrasekhar and Ghosh, 2007).

Owing to the perceived lost revenue, the Finance Ministry announced a Minimum Alternate Tax on the book profits of developers and units operating in SEZs in the 2011-12 Budget. The Commerce Ministry, however, wants to see a roll back of this tax and sees SEZs as “engines of growth” (Pannu, 2011). This points to differences between the Finance Ministry and the Commerce Ministry on the issue of SEZs.

In fact, Arunachalam (2010, p25) shows that the investment as of 2009 in approved SEZs stood at £416million, and not the figures cited by the Finance Ministry. He argues (2010, p20) that Indian SEZs failed to attract FDI as it would have liked because firstly, India has not used SEZ policies to test reforms which would later be adopted nationwide; secondly, Indian SEZs are small in size (especially when compared to their Chinese equivalents), and finally, because of the lack of labour market flexibility.

ii. Exports:

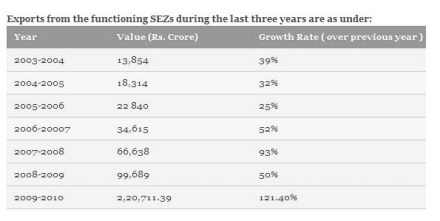

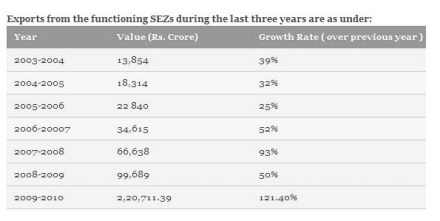

The Ministry of Commerce and Industry claimed that the value of exports from functioning SEZs increased from £1.9billion in 2003-04 to £30.6billion in 2009-10 (exchange rate £1 = INR72 as of 16th March, 2011). The growth rate of exports over the previous years increased from 25% before the SEZ Act, 2005 to 52% after its implementation, and it stands at 121.40% in 2009-2010 (SEZ India, 2011a, Export Performances). Note that these figures are inconsistent with the estimates of

losses by the Finance Ministry.

An example of a successful SEZ in this regard would be the Mundra SEZ. This SEZ houses India’s largest private port, has been most successful in seeing an increase in exports. It is expected to handle 100m tonnes of exports by 2013, with a growth rate of 40% in these years (Thakkar, 2008).

However, the Comptroller and Auditor General of India has pointed out that most of the SEZs sell goods within the country as “deemed exports” rather than actually exporting them overseas. This seems plausible as the exponential rise of exports from SEZs corresponds with stagnant national exports. The Finance Ministry speculates that some units have merely shifted to these zones from the DTA to avail tax benefits (Pannu, 2011).

Source: SEZ India, 2011a, Export Performances

iii. Employment generation (or the lack thereof):

Proponents of SEZs have claimed that SEZs lead to employment generation, in addition to exports. While the total employment by all types of SEZs across India as of 2008 was about 370,000 (Reddy, Prasad and Kumar, 2010, p87), Mahanta (2010, p199) shows that acquisition of agricultural land by SEZs lead to a fall in food-grain output and agricultural employment. Importantly, he shows that this fall in agricultural employment is not offset by the increase in employment in SEZs.

Another point to note is that compared to countries around the world, Indian SEZs have not seen a high proportion of female workers. In 2003, only 37% of the workforce was female (Varma, Prasad and Krishna, 2010, p320-322). The claims of benefits of the generation of employment by SEZs are hence called into question.

The Social Experience

i. Land acquisition and displacement

Land acquisition is the ‘hot topic’ of India’s SEZ policy. The SEZ Act, 2005 makes no mention of it. The out-dated Land Acquisition Act, 1894, is applicable in this regard. Even the Land Acquisition (Amendment) Bill, 1998 has come under fire from for several shortcomings. For instance, land losers could have their land acquired even if a stated compensation isn’t paid (Asif, 1999, p1564).

Land acquisition is especially contentious and problematic when the land being acquired is populated with people living off the land, which is often the case with agricultural land, as was the case in Nandigram, West Bengal. In addition to this, Chandrasekhar and Ghosh (2007) argue that real-estate developers can engage in major land grab in the guise of setting up SEZs as the SEZ rules require only 25 per cent of the land to be used for industrial processing purposes.

While approved SEZs are to consume 95,000 hectares of land, (Balasubramanian, 2010, p53), the Ministry of Commerce stated that as of 2008, the land allocated to SEZs was about 0.070% of the total land area and 0.128% of the total agricultural area of the country (Reddy, Prasad and Kumar, 2010, p87). While this may seem low, it is has proven to be problematic because of the high population density in some of these areas.

An illustration of the flawed acquisition mechanism by the government would be the case of the state of Andhra Pradesh, where land is being acquired from the poorest people who had been earlier allocated land by the government in “land-for-the-poor schemes”. Legally, this land belongs to the government, so the government takes it back often without compensation on the behalf of SEZ developers (Oskarrsson, 2010, p368).

On the other hand, the Commerce Ministry has cited examples of how rise in land rates in barren, unproductive land has brought wealth to the poor and SEZs have brought infrastructure to the hinterland, as is the case with Mundra in the state of Gujarat (Bhatt, 2007). The wastelands in the coastal regions of Gujarat are mostly owned by the government, hence leaving out land acquisition out of the picture. Moreover, states like Tamil Nadu have seen the rural population welcome SEZs, because several years of social upliftment by the government has made the populace less dependent on agriculture for their livelihood (Murugesan and Bandgar, 2010).

ii. Labour relations

While the SEZ Act, 2005 makes no mention of changes in labour law, Tanwar (2010, p231) writes that changes to the prevailing pattern of application of labour laws have been made in SEZs. All units operating in SEZs are categorised as “Public Utility Service”, meaning that many labour laws become irrelevant. A Public Utility Service is defined to be a service that is of great value to the society, and the lack of provision of which can affect the life of everyone. In this case, employees have to give a 14 day notice before going on strike. Additionally, employees in SEZs don’t have protection in the form of a notice period or compensation against retrenchment. It follows that employees will be reluctant to raise a voice against their employers when the need arises. Moreover, employers in SEZs have the right to change the terms and conditions of service at any point of time. Mahanta (2010, p200) raises concern regarding the lack of labour unions, stating that the possibility of fall in real wages is high, although experience shows that SEZ wages are at par with non-zone wages (Varma, Prasad and Krishna, 2010, p326).

Conclusion

This essay has dealt briefly into a few contentious issues that arise with the establishment of SEZs in India. With significant employment not being generated, and with no real rise in national exports has taken place, the rationale of this establishment is called into question. The issue remains volatile, as was seen in the case of Nandigram, where the conflict continued to simmer after the scrapped its plans to establish the SEZ there (Dohrmann, 2008, p76).

However, governments are unlikely to give up on establishing SEZs, and it is imperative that laws are amended in order to make trade and investment flourish without disempowering the people who are displaced or the workforce in SEZs. The Land Acquisition Act of 1894 need to be looked into, and a transparent rehabilitation law needs to be put in place (Dohrmann, 2008, p79). In fact, the people need to be made stakeholders in the progress of the nation. Failure to do so may further prove former Indian Prime Minister VP Singh correct in his assessment of the SEZ policy of India, when he said (Dohrmann, 2008, p1), “the current promotion of SEZs is unjust”, and that it acts as a “trigger for massive social unrest, which may even take the form of armed struggle.”

__________________________________________________________________________________

References

- Arunachalam, P., 2010. “Special Economic Zones and Foriegn Direct Investment in India and China”. In: Arunachalam, ed. Special Economic Zones in India. Serials Publications, New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-8387-336-9

- Asif, M., 1999. “Land Acquisition Act: Need for an Alternative Paradigm”. Economic and Political Weekly June 19, 1999 Balasubramaniyan, R., 2010. “An Econometric Analysis of Special Economic Zones in India”. In: Arunachalam, ed. Special Economic Zones in India. Serials Publications, New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-8387-336-9

- Bhatt, S., 2007. “Rivalry Between Business Houses has blown up the SEZ issue”. Rediff News 21st Feb, 2007. [online] Available at: http://www.rediff.com/money/2007/feb/21sez.htm [accessed 18th March, 2011]

- Chandrasekhar, C.P., and Ghosh, J., 2007. “SEZs in India: The Record So Far”. Business Line, 27th November, 2007. [online] Available at http://www.thehindubusinessline.in/2007/1/27/stories/2007112750070900.htm [accessed 15th March, 2011]

- Dohrmann, J. A., 2008. “Special Economic Zones in India – An Introduction”. ASIEN 106 (January, 2008) p60-80 [online] Available at http://www.asienkunde.de/articles/a106_asien_aktuell_dohrmann.pdf [Accessed 16th March, 2011]

- Dutta, M., 2009. “Nokia SEZ: Public Price of Success”. The Economic and Political Weekly, 3rd October, 2009. Vol XLIV no. 40

- Guangwen, M., 2003. The Theory and Practice of Free Economic Zones: A Case Study of Tinajin/People’s Republic of China. Peter Lang ISBN 0-8204-6508-9

- Mahanta, A., 2010. “Special Economic Zones and its Impact on Agriculture and Employment in India”. In: Arunachalam, ed. Special Economic Zones in India. Serials Publications, New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-8387-336-9

- Manoj, P. K., 2009. Special Economic Zones in India: Financial Inclusion: Challenges and Opportunities. Serials Publications, New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-8387-275-1

- Muchlinski, P., 2007. Multinational Enterprises and the Law 2nd Ed. Oxford University Press

- Murugesan, P., and Bandgar, P. K., 2010. “Land Acquisition for SEZs in India: Theoretical Perspective”. Southern Economist, 1st August, 2010 [online] Available at: http://www.vesasc.org/Economics_-_Murugeshan_Sir.pdf [Accessed 19th March, 2011]

- Nagayya, D., and Rao, T. V., 2010. “Special Economic Zones For Raid Insutrlization and Regional Development: Progress and Concerns”. In: Arunachalam, ed. Special Economic Zones in India. Serials Publications, New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-8387-336-9

- Oskarsson, P., 2010. “Zoning Andhra Pradesh: Land for SEZs via tha Land for the Poor Program”. In: Arunachalam, ed. Special Economic Zones in India. Serials Publications, New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-8387-336-9

- Pannu, S.P.S, 2011. “Ministries in a tug of war over tax on SEZs”. Business Today, 14th March, 2011 [online] Available at: http://businesstoday.intoday.in/bt/story/ministries–fight–over–taxon–special–economic–zones-(sezs)/1/13883.html [accessed 14th March, 2011]

- Reddy, P., Prasad, A., and Kumar, P., 2010. “Generation of employment by Special Economic Zones in India”. In: Arunachalam, ed. Special Economic Zones in India. Serials Publications, New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-8387-336-9

- Sharma, N. K., 2009. “Special Economic Zones: Socio-Economic Implications.” Economic and Political Weekly 16th, May, 2009 vol. XLIV no. 20

- SEZ India, 2010, “SEZ Rules incorporating amendments upto July, 2010”. Ministry of Commerce and Industry (Department of Commerce), Government of India [online] Available at: http://sezindia.nic.in/goi–policies–sra.asp [Accessed 14th March, 2011]

- SEZ India, 2011a. Special Economic Zones in India, Ministry of Commerce & Industry (Department of Commerce) [online] Available at http://sezindia.nic.in/ [Accessed 15th March, 2011]

- SEZ India, 2011b. “ListofFormalApprovalsgrantedundertheSEZAct,2005, 2011”. Ministry of Commerce and Industry (Department of Commerce), Government of India [online] Available at: http://sezindia.nic.in/writereaddata/pdf/ListofFormalapprovals.pdf [Accessed 14th March, 2011]

- SEZ India, 2011c. “In Principle approvals granted under the SEZ Act, 2005”. Ministry of Commerce and Industry (Department of Commerce), Government of India [online] Available at: http://sezindia.nic.in/writereaddata/pdf/Listofin–principleapprovals.pdf [Accessed 14th March, 2011]

- SEZ India, 2011d. “SEZ: Statewise Distribution”. Ministry of Commerce and Industry (Department of Commerce), Government of India [online] Available at: http://sezindia.nic.in/writereaddata/pdf/StatewiseDistribution–SEZ.pdf [Accessed 14th March, 2011]

- SEZ India, 2011e. “SEZ: Sectorwise Distribution”. Ministry of Commerce and Industry (Department of Commerce), Government of India [online] Available at: http://sezindia.nic.in/writereaddata/pdf/Sector–wise%20distribution–SEZ.pdf [Accessed 14th March, 2011]

- Tanwar, S., 2010. “Relevance of Labour Laws in Special Economic Zones”. In: Arunachalam, ed. Special Economic Zones in India. Serials Publications, New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-8387-336-9

- Thakkar, M., 2008. “Mundra Port: Anchored to Success”. The Economic Times 12th Nov, 2008 [online] Available at: http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2008-11-12/news/28448158_1_mundra–port–sez–adanis–biggest–port [Accessed 19th March, 2011]

- Tantri, M. L., 2010. “Import Dependency of Special Economic Zones”. The Economic and Political Weekly 4th September, 2010 Vol. XLV no. 36

- The Telegraph, 2007. “Red-hand Buddha 14 killed in Nandigram re-entry bid”. The Telegraph, 15th March, 2007 [online] Available at http://www.telegraphindia.com/1070315/asp/frontpage/story_7519166.asp [accessed 14th March, 2011]

- The World Bank Group, 2008. “Special Economic Zones: Performance, Lessons Learned, and Implications for Zone Development”. The World Bank Group, April, 2008 [online] Available at: http://www.ifc.org/ifcext/fias.nsf/AttachmentsByTitle/SEZpaperdiscussion/$FILE/SEZs+report_April2008.pdf [accessed 14th March, 2011]

- The Land Acquisition Act, 1894. Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India, 1st Spetember, 1895 [online] Available at: http://dolr.nic.in/hyperlink/acq.htm [accessed 16th March, 2011]

- The Special Economic Zones (SEZ) Act, 2005. Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India. 23rd June 2005 [online] Available at http://sezindia.nic.in/goi–policies.asp [Accessed 13th March, 2011]

- UNIDO, n.d. “Export Processing Zones: Principles and Practice”, United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. [accessed from the British Library of Political and Economic Science, LSE]

- Varma, A. V. N., Prasad, J. C., and Krishna Y. R., 2010. “Special Economic Zones – The Socio Economic Dimensions and Challenges.” In: Arunachalam, ed. Special Economic Zones in India.

Serials Publications, New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-8387-336-9

![Saudi US ambassador Adel al-Jubeir (seen here seated with former US First Lady Laura Bush and King Abdullah) [Photo: DS] US agents state that a "significant terrorist act" linked to Iran which would have included the assassination of the Saudi US ambassador Adel al-Jubeir (seen here seated with former US First Lady Laura Bush and King Abdullah) has been foiled recently.](https://inpecs.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/picture2-e1330871416718.jpg?w=440)